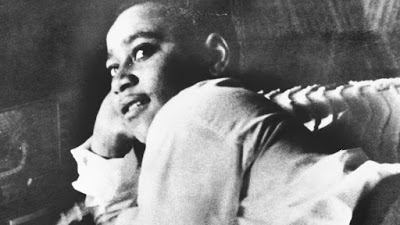

I want to start this post off with the fact that nothing about this was easy to write. It took me two long months to complete every idea I had in my head on how I wanted this post to appear. Unlike the Michael Jackson case, this one hits home more, because I am a black young person, and I have such a soft spot for children. He was fourteen years old, a baby, and a playful, humorous one at that. He was scared, expressed that he wanted to go home days before his abduction and subsequent death; and the killers were nothing but shells of should-be matured adults. They were not, needless to say. Not even the seed of it all—the woman who accused this young boy of flirting with her in such an inappropriate and disturbing way. Carolyn Bryant lied and she knew she lied, fully confessing in an interview with Timothy B. Tyson in 2008, found in his book, The Blood of Emmett Till:

“Nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.”

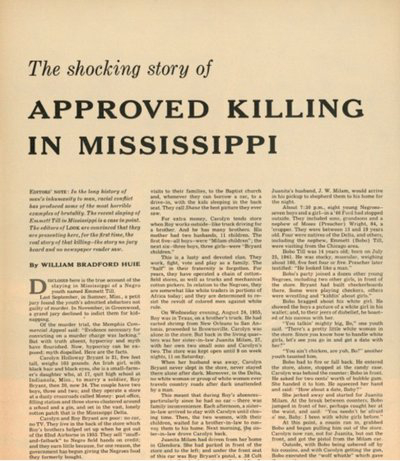

When Emmett Louis Till, who had just turned 14 a month earlier in July, asked his mother if he could go with his older and younger cousin to go see their great uncle, Mose Wright in Money, Mississippi, he had no idea he would be kidnapped from his uncle’s home, beaten, shot, tortured, mutilated, killed, and then thrown into a river with a cotton gin wrapped around his neck to weigh him down, for whistling at a white woman. It was summer break, I’m assuming, and the boy was probably ready for some fun. He was close to his cousins, especially Wheeler Parker, older by two years. He looked up to him. So when the opportunity to visit his great uncle arose, there was no way he could let that pass.

This had to be such a tragic and irreversible moment that Mrs. Till, his mother, could never take back. Her worse fears had happened just days after sending him off on the train. The next time she saw her son, he was disfigured, mutilated, and bloated beyond recognition in a wooden box.

Till’s mother was quoted talking about the remains of her son by stating that “there was no way I could describe what was in that box. No way. And I wanted the world to see.”

I first learned about Emmett Till in the eighth grade. I flipped through a book I received from some book fair (these went on a lot at my middle school) and found various photos of black people who contributed to the growth of Black History. I found photos of lynchings, murder victims, Martin Luther King, Jr., and many others. Even some white people who died in the fight for us to have equal rights. But when I found Till’s section, which didn’t include the gruesome photo of his body (I remember looking it up with a fellow classmate), I couldn’t shake it off.

Maybe because he was around my age (I was 13.) Maybe it was because I was black. Maybe it was because my dad was from Mississippi, which was known for being very racist, and I loved visiting my grandparents there every summer. I’m not entirely sure. But I knew I felt this tug at something that I always knew was there; I don’t want to be black. If blackness meant death, and a gruesome, painful one, then I wanted to be something else.

The state of Mississippi tried to cover up hatred. When Emmett’s body was retrieved put of the Tallahatchie River by a young white boy, Mississippi ordered that the box containing his remains was placed in not be opened and be buried immediately. Roy Bryant (then husband of Carolyn Bryant) and his half-brother J.W. Milam, confessed to killing Emmett in Look Magazine in 1956, sharing: “Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless. I’m no bully; I never hurt a nigger in my life. I like niggers — in their place — I know how to work ’em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, niggers are gonna stay in their place. Niggers ain’t gonna vote where I live. If they did, they’d control the government. They ain’t gonna go to school with my kids. And when a nigger gets close to mentioning sex with a white woman, he’s tired o’ livin’. I’m likely to kill him.”

It’s interesting how Milam and Bryant were able to confess this just a year after Emmett’s murder with no remorse or guilt. No one believed them that they hadn’t killed Emmett. But no one was going to speak out against them. It was more of a sweep under the rug, something people were bothered about for a bit. However, murdering black people was a norm, as lynchings often were announced in churches in between sermons and had tickets sold and barbeques following.

Emmett’s body was retrieved by his mother and sent back to Chicago via a train. It was then opened by a funeral home director named A. A. Rayner, who embalmed the body without retouching the face too much. “No, leave it the way it is.” Mamie Till-Mobley told Rayner. “Let the people see what I see.”

No one but the witnesses of a lynching saw what the dead, mutilated, hanging body looked like, swinging from a large tree branch via a rope. The witnesses were usually perfect, god-fearing, white people, who most likely had just come from church. So when Mrs. Till-Mobley decided to keep her son’s casket open during the four days of his funeral, black people from all around America, grew furious.

|

| Emmett earlier in July 1955 and Emmett’s battered, mutilated body in August 1955. |

The trial attracted much attention. However, the attention wasn’t enough to convict the two gentlemen. In 1955, an all-white jury found the men not guilty. They celebrated with a crowd of cheering bystanders and told the reporter the thing they were the most glad about: “I’m just glad it’s over”. Both french-kissing their wives in front of the camera.

This passivity from Mississippi still marks it as a state riddled with white supremacy and the KKK. I recall being told myself, as a young girl visiting grandparents in a rural part of Mississippi, not to go outside during dark hours because of KKK members and people with guns. I didn’t understand it then, as my parents and family members used vague language, but looking more into this lynching, I realized why.

I called my grandpa a little while before Thanksgiving to thank him personally for deciding to stay in Mississippi and deciding to stay strong during the Jim Crow era. While he is 85, he has a sharp mind and still remembers much of his younger days. I repeated stories he had most likely heard and seen millions of times: not being able to look at, speak to, or be next to a white woman, walking home at night and fearing you’ll be shot, not being able to just walk into any store you’d like to go to because it was segregated, etc. He would reply with his signature “oh yeah”s, because he knew what I had mentioned were still familiar to him. “I remember one time I was comin’ home, and this white boy had a gun in his hand, and he said “I hope he can run ‘cus I’mma shoot him.” He never did nuthin’ tho, but a lot of times I prayed while I walked home so nothing would happen to me.”

This sent so much fear down my spine. Imagine walking home and being scared that you’ll be shot where you stand. I am pretty sure this wasn’t the first time he’s been threatened by a white person. Although he’s expressed thankfulness for times now being so different, he still remembers the fear. It’s apparent that black people today seem to forget that being black in the early 1900s was a death sentence; that we were not supposed to have the luxuries we inhabit now. I think of how frequent I love to visit the library. In the 1950s, in Mississippi, I would not have been able to do this. My creativity, which is fueled by books and paper, would have greatly been stunted.

But there were men like Martin Luther King Jr., who eventually died for his strong belief that black people are people as well. Or what about Rosa Parks who was fueled by Emmett’s death and stayed put in her seat. Emmett Till’s murder galvanized the civil Rights movement for black America. And with this being Black History month, I want to keep a heart open and thankful for the lives that went before me. As a black woman, and a future mother to black children, I want them to be aware of boys like Emmett Till and women like his mother, who sacrificed many for black children to enjoy the mindless pleasures and luxuries we have today.

But there were men like Martin Luther King Jr., who eventually died for his strong belief that black people are people as well. Or what about Rosa Parks who was fueled by Emmett’s death and stayed put in her seat. Emmett Till’s murder galvanized the civil Rights movement for black America. And with this being Black History month, I want to keep a heart open and thankful for the lives that went before me. As a black woman, and a future mother to black children, I want them to be aware of boys like Emmett Till and women like his mother, who sacrificed many for black children to enjoy the mindless pleasures and luxuries we have today.